By Mark Vargas, Editor-in-Chief & Opinion Contributor

A quiet but dangerous crisis is unfolding across our southern border – one the mainstream press barely acknowledges, and one the Biden administration spent years ignoring.

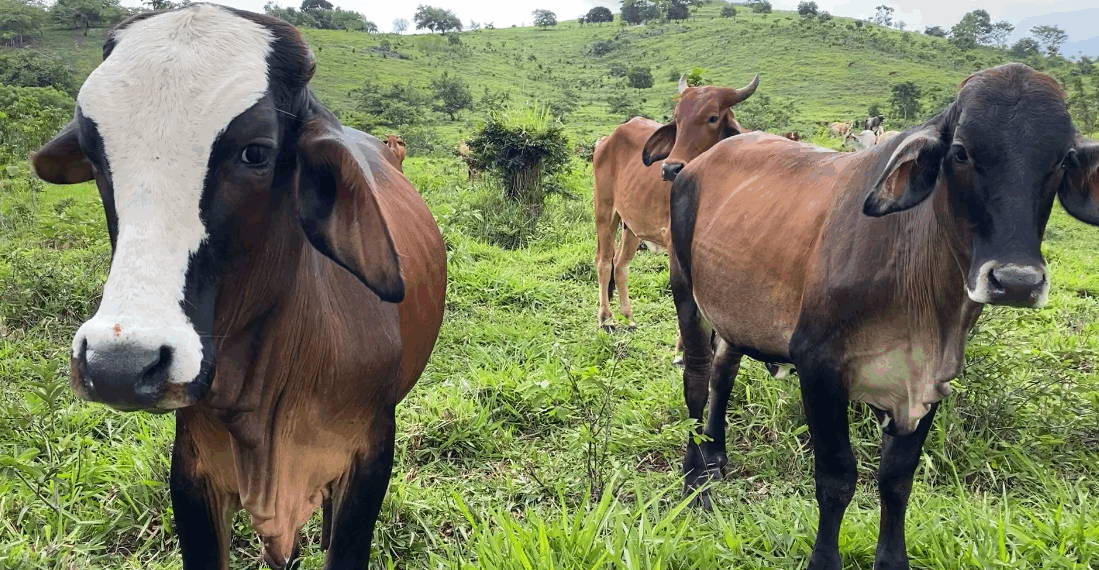

It’s the rise of narco-ranching: cartel-run cattle networks that launder drug money, traffic stolen livestock, enable massive environmental destruction, and now threaten the U.S. food supply with deadly pests.

As of December 12, 2025, the U.S. border remains closed to live cattle imports from Mexico because of the New World screwworm outbreak. The parasite – eradicated decades ago through U.S. leadership – made a full resurgence in 2025 across Mexico and Central America.

The USDA has repeatedly shut down imports after brief reopenings in February and July when the disease continued spreading north. But while Mexican officials insist the situation is “contained,” the facts tell a far darker story.

Behind the outbreak is a booming criminal industry. Mexican cartels and their Central American partners now smuggle an estimated 800,000 cattle a year, worth more than $320 million, using the livestock trade as a money-laundering pipeline.

Weak traceability and corrupt checkpoints allow diseased or stolen cattle to flow freely into Mexican markets – and toward the U.S. border. Cartels openly forge ear tags, a thriving $18 million black market, undermining every quarantine Mexico claims to enforce.

Nowhere is this more evident than Nicaragua, where narco-ranching has gutted protected jungles like the Bosawás reserve. Ortega’s regime, friendly to cartel interests, has allowed entire corridors to be carved open so illegal herds can move toward Mexico.

Nicaragua logged 124 screwworm cases in 2024-2025, and infected cattle then moved north via Honduras and Guatemala before blending into Mexican herds in Chiapas and Veracruz – both now outbreak hotspots.

Mexican ranchers themselves are sounding the alarm. Experts inside Mexico’s own national cattle union warn that smuggling – now a “transnational crime” – directly fueled the 2025 screwworm resurgence. By mid-year, over 500,000 non-compliant ear tags had been seized in Chiapas alone.

This is not just an agricultural problem. It is a cartel problem. And cartel problems become American problems.

Chicago offers a stark reminder of how cartel networks embed themselves deep inside American supply chains. For more than two decades, federal law enforcement has identified Chicago as one of the primary U.S. distribution hubs for cartel-supplied cocaine, heroin, methamphetamine, and, more recently, fentanyl.

The money flow was staggering. Prosecutors documented roughly $700 million per year in drug proceeds generated through Chicago operations, with an estimated $1.8 to $2 billion in cash smuggled back south via couriers and laundering routes detailed in court records.

What we are seeing now in cattle smuggling mirrors the same cartel infrastructure that once flooded Chicago neighborhoods with narcotics.

Narco-ranching follows the same cartel playbook.

President Trump has made clear that the era of looking the other way is over. His administration has already taken historic steps against cartel networks, designating them as ‘narco-terrorist’ organizations, launching precision strikes on smuggling routes, and insisting that disease outbreaks tied to criminal activity will not be allowed to endanger American ranchers or consumers.

That is why USDA’s monthly reviews continue to keep the border closed. And it’s why Trump’s commitment to crush cartel influence – not accommodate it – is the only credible path to restoring safe, legal, and traceable cattle trade.

The experts are blunt: unless the U.S. confronts narco-ranching with real enforcement and real political will, another outbreak is inevitable – and American ranchers and consumers will pay the price.